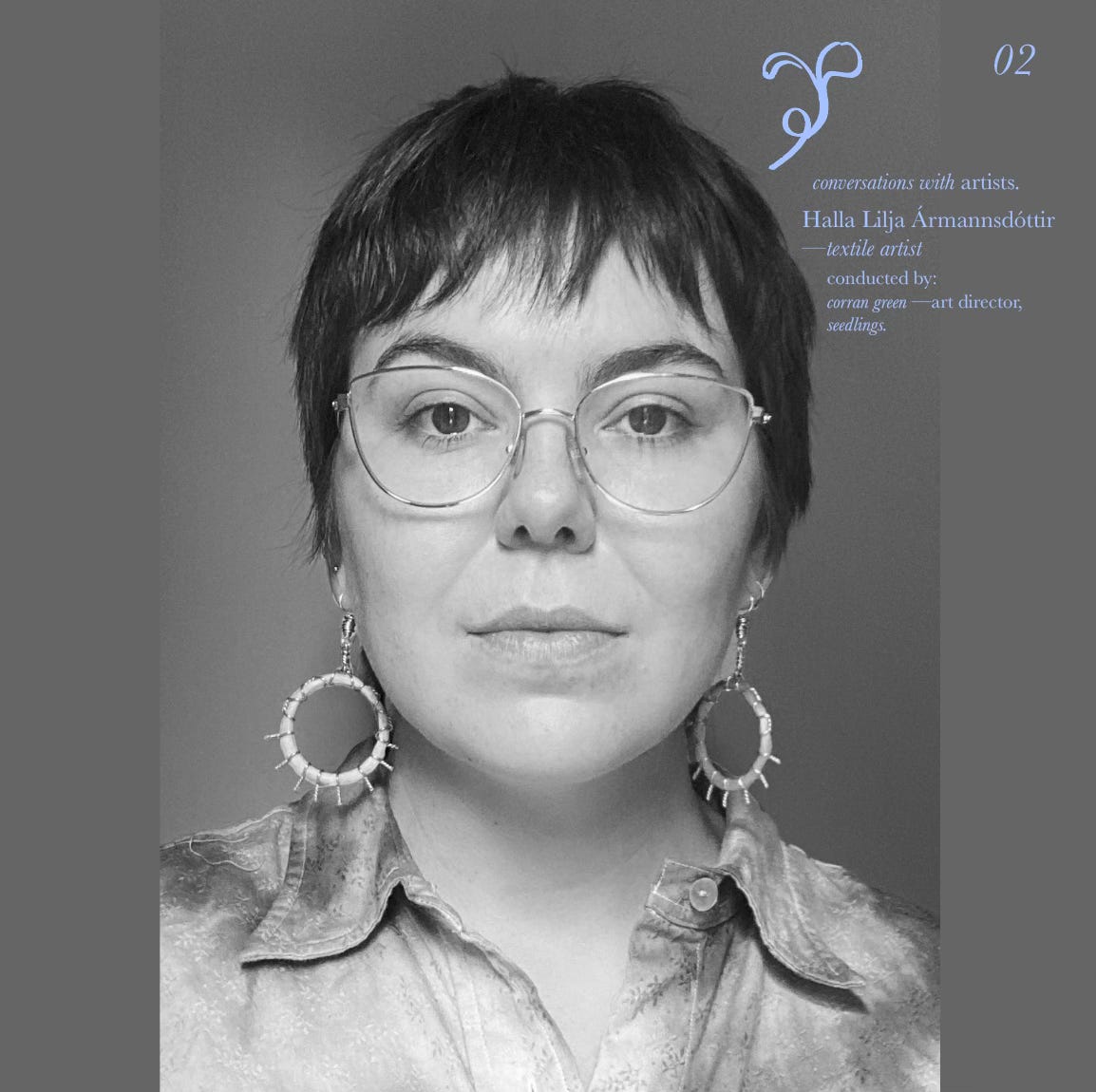

a seedling series—conversations with...HALLA

‘She is I: The Knitting Experience’—Halla Lilja Ármannsdóttir. (textile artist)

Halla is an Icelandic textile artist and knitwear designer whose work weaves memory, landscape and tradition into sculptural form. Her pieces range from horsehair jewellery, to textile sculptures, wall hangings, and mostly she creates knitted garments that feel like walking sculptures in there own right — Her work reflects her environment and heritage in a tactile, transformative way. This summer, Halla opens her solo exhibition at the Textile Museum in Iceland. Titled ‘She is I: The Knitting Experience’, the year-long show unfolds as a timeline of her ever evolving practice — a story of material, memory, connection and future-making told through fibre.

I have had the privilege of being asked to Curate her show—which is such an incredible honour, and were both eager to see how it turns out. This interview is a short conversation about her exhibition and look into her practice.

—Corran Green, Art Editor.

You Can see the full video here:

The exhibition opened on June 7th at the Heimilisiðnaðarsafnið—the Icelandic Textile Museum.

‘...A dialogue of knitting expressions in the form of fashion, art, sculpture and jewellery. Exploring nature, material and family lineage...’

“You’ve described knitting as something that’s been with you since childhood—what do you remember about those first moments?”

I remember my mom kind of wanting me to knit, to slow me down, you know cause I was all over the place, I’ve always had a lot of energy. It was something for her to have me in the same place for a while because then I could just focus on the (one thing).

The first project I remember that she made me do were these knitted mittens that I made for my dad for Christmas. I don't think they were gonna fit, ever. I remember because you always had to wash them and then set them before you let them dry and I was so eager and they hadn't dried so I took them and put them in the oven, and I started cooking them. I was hoping that they would be ready for him when he would wake up, which to my surprise did not work. I've always been this solution based problem-solving (person). I don’t remember what happened to them. I just remember that my mom came downstairs and I think she smelled them and she was so furious, “(after) all of this time making these things. How would you know though? I mean he must've been young as well?” Around 5 or 6. I really wish they were somewhere. I think it was good for me to have something to do with to focus on like this.

“Can you tell me in particular how this craft has helped mould your relationships with the women in your family?”

I think this has mostly been a relationship between my mum and me. I think she just taught me a lot of things through this craft. How to learn to do something new, she taught me how to fail miserably and to still continue. (How) to fix my own mistakes. She was quite a tough mom in regards of like showing me how to do it once twice, maybe two, three times and then leaving me (to work it out). I think you know it created a relationship (where) I could always find knowledge within her (and) when I was doing my own things I could (ask for her advice) it's good to have this kind of interaction that is not about necessarily family or like housework or like your typical things but a (shared craft).

You might be teaching each other. “it's (creative) and practical isn't it?” When would be creating a sweater she would ask me about my opinion that we would chat about these things and nobody else could partake in these discussions, they were ours. “You wanted each others opinion, and you respected what the other had to say” Yes.

My Grandmothers both knit, (but) because they lived so far away I didn't really necessarily have that kind of relationship with them. Even though now my grandma will ask me to help her with things. But they made me sweaters and socks and mittens and things I wear all the time, they have always knitted.

“From an outsider you can see how important knitting is within Iceland as a craft” I think what makes it so important to us is that all of us school start learning (to knit) as kids. It’s taught in elementary schools, you start learning textiles when were in forth grade, then you have to study it until at least seventh grade and then you can choose if you want to continue.

I think to teach kids how to use their hands like this, to teach how to create their own clothes, and to be connected to this craft it makes us all understand it, I guess on some specific levels. “…and respect it because it takes a really long time —respect your clothing (enough to) learn how to mend it”

“I remember getting really frustrated (with the knitting machine) I remember you saying to me that knitwear requires so much patience… and it will take time but you will learn how to be patient by knitting”.

“How do you feel that your background in music shaped structure of your textile work today?”

I started playing the piano when I was around 9 and played for about 7 years. When I played the piano, I was wild. It was hard to make me do specific things, I wanted to play my own way, play to my own rhythm. I did not want to learn musicology or even follow the metronome, I just wanted to have fun and I found myself really enjoying jazz.

When I was developing my projects in LCF I did all of these abstract drawings and then I would go and make a cable swatch, there was a disconnect between the two. I have a traditional background in knitting and I was so stuck on the rules. Kind of like classical music, everything had to be perfect. I remember our tutor telling me that only if I would manage to translate my images to my knitting I would get somewhere, pushing it into something unexpected. And so, I started focusing on how I used to improvise with jazz and put that into my knitting, I called them my jazz knits.

“Your work blends traditional techniques with innovation, can you tell me about your hand knitting in contrast with your Kniterate digital knitting, and how they lend themself to each other?”

I think about everything in terms of tools—what each tool can give me and how it can help realise an idea. There are lots of things I want to make, but I always have to figure out the right way to execute them. I often come back to hand knitting, even though I don’t really do it much anymore. Especially not the complicated cable work on 2.5 or 3mm needles, which I used to love as a kid—that kind of thing has ruined my hands. So now I try to be more careful about what I choose to do. It has to make sense, not just be a challenge for the sake of it.

Over time, my practice has developed into a specific language of patterns and stitches. I still love traditional techniques, and I’m constantly referring back to books like the Japanese Knitting Stitch Bible—which I recommend to everyone. I don’t think we should exclude something just because it’s traditional. There’s so much beauty there, and we can find new ways to use it. Hand knitting has really trained my brain—it’s taught me how things fit together, what works structurally, and how to think in that way. I try to bring that same thinking into my machine knitting. For me, it doesn’t matter which machine I’m using; the expression is still mine. I don’t feel like I lose my voice to the tool, and that feels really important. I’ve noticed that when you have that foundation in craft, you bring something different to the machine. There’s a depth to the work that comes from building on that knowledge. You can tell when someone understands those fundamentals—it shows up in the details.

“Can you tell us about how you first started experimenting with horsehair and how this process came about?”

I started working with horsehair during the COVID lockdown, when I was unexpectedly stuck at my parents’ house without any materials. That limitation forced me to think differently—I couldn’t over-plan or control everything. Instead, I had to work with what I had, which made the material feel more like a collaborator than a choice. Around that time, I saw an exhibition in Reykjavík honouring Ásgerður Búadóttir. Her work—and others’—used horsehair in weaving. I wondered what it could look like through my own, non-weaving background. That curiosity led me to a slaughterhouse, where I sourced my first horse tails. They were messy, smelly, and intimidating—but I learned to process and clean them myself, outside in freezing February weather.

Eventually, I began crocheting the hair, combining it with wire to give it structure. That’s when it started to evolve into jewelry. I’ve come to love the material’s difficulty—how it requires patience and care. Each strand is unique, and sometimes I only get one or two pieces from a special one. The work taught me the value of simplicity and letting the material speak. If I’m using horsehair, I want people to see that. It’s coarse, raw, and strangely beautiful—and I still find it endlessly inspiring.

“Do you approach each piece with a story already in mind, or does the narrative unfold through the making?”

It really depends on the piece. Sometimes I start with a clear idea—like knowing I want to make a sweater or a dress—because I like staying close to familiar forms. Other times, the idea evolves slowly, like with the big poncho, which sat in my head for a year before I had the time and reason to make it. That one became more than just clothing—it turned into an art piece. But you don’t always know how it’ll turn out until it’s done. Knitting is unpredictable like that; it transforms throughout the process. Even something like blocking, it makes a huge difference once I saw the results. Mistakes happen all the time, but they’re part of how the work grows.

“Where do your materials come from—and how important is origin and texture to your process?”

Texture and origin are hugely important to me. I mostly work with natural fibers—I’ve never been drawn to synthetics. They just don’t feel right to work with, and I like the idea that my pieces can break down naturally over time. My mom, who’s a textile teacher, always said if you’re putting that much time into making something, use good material—and I’ve carried that with me. I get a lot of yarn through family and community, especially back in Iceland. I’m quite picky, but it’s intuitive—I know it when I see it. I love mixing textures, like rough Icelandic wool with something soft and delicate. That contrast creates a kind of tension in the work that I really enjoy. It's not just about how it looks—it’s about how it feels and lives over time.

“Your pieces often feel tied to the Icelandic landscape—do you think of them as physical expressions of the land, or something more internal and emotional?”

It’s really both. My work is rooted in emotion, but nature is the language I use to express those feelings. I see the landscape as alive, and my pieces are like emotional snapshots—translating what I feel into form.

It's a way of understanding myself through nature. That’s also why each shape ends up so different—because it begins with a feeling, not a fixed design.

“What role does the idea of heritage or generational memory play in your practice?”

It’s always present. I don’t feel full ownership over what I make, because so much of it comes from what’s been passed down—skills, stories, ways of living. My family comes from a tough, remote part of Iceland, and those stories—like my great-aunt dyeing wool with wildflowers, or my grandma knitting me a sweater I still wear—are part of what I carry into my work. It’s not just craft; it’s memory, survival, and connection.

“Have you seen a shift in the investment of crafted pieces ?”

It’s hard to say. There’s always been a community that values craft, especially in places like Iceland, but I don’t know if that’s growing or just more visible in the circles I’m in. Craft is so personal—both in making and buying—so it’s not always about trends.

My pieces take a lot of time, so they come at a higher price point, and I often have to wait for the right person to come along—someone who’s been thinking about it for months, saving up, wanting something meaningful. And that’s actually quite beautiful. I think people are becoming more intentional with what they buy, especially with the rise of secondhand culture and a shift toward minimalism and quality. To make things more accessible, I also create smaller, more affordable pieces like the horsehair jewellery. A lot of makers do that—it helps sustain the bigger, slower projects. But even in those smaller things, the craft and technique still matter. They carry the same care, just in a simpler form.

“There’s a quiet strength in your work—what stories or emotions do you hope people feel when they encounter it?”

I think the core of it is connection—both with ourselves and with the natural world. My work tries to reflect that calm, grounded feeling you get when you’re completely present—like standing by the ocean, everything moving in its own rhythm, and you’re just part of it. There’s a balance I’m always drawn to—between softness and strength, peace and power—just like nature itself. A wave can be gentle or destructive. That contrast fascinates me and reflects how I experience the world. When I lived in Iceland, I walked our family dog every day, in all weather—storms, snow, sun. That daily rhythm forced me to meet nature as it was, not as I wanted it to be. I think that shaped my work: it's about being open, present, and letting things be as they are.

“What has it meant to you to show your work here at the Icelandic Textile Museum—especially within a space so rooted in history and tradition?”

It’s a huge honour. I was genuinely surprised to be asked—I'm still early in my career, and it feels surreal to be trusted with a solo exhibition in such a respected space. This is the museum’s only rotating exhibition space, so to have my work featured as the contemporary voice within a setting so rich in textile history is incredibly meaningful. It’s both exciting and nerve-wracking. Sometimes I wake up with nerves, but I think that just shows how much it means to me. It’s not something I take lightly—having the chance to add to this lineage, even briefly, is something I’ll carry with me for a long time.

“Can you tell me what you want to bring to the exhibition space, what impact you hope to make?”

I want to create a space that feels alive with stories—where people walk in and feel a presence, a character, maybe a question: Who is she? I’m interested in how knitted textiles can hold emotion, interact with one another, and suggest a kind of personality or spirit beyond myself. At its core, the exhibition is about inviting people to experience knitting in a new way—not just as a craft or a garment, but as something sculptural, expressive, and dimensional. I use traditional techniques, but I’m trying to push them beyond their usual form and function. I want the space to feel intimate, unexpected, and full of quiet energy.

“Is there a particular piece in this exhibition that feels especially personal to you, or holds a secret story?”

Yes—there’s a piece called Meðvirkni, which loosely translates to “codependent.” I made it while trying to understand that feeling, to give it a physical form. It includes horsehair, and originally I positioned it so the hair flowed downward—what felt “correct” to me emotionally. But someone saw it and said they preferred it upside down. And I thought—well, maybe that’s fitting. The piece is literally turned in a way that goes against my instinct, but that's part of the idea: giving in, adapting, bending to someone else. So now it hangs "right side up" for everyone else, but it still feels upside down to me. It’s uncomfortable, a little eerie—and that captures the emotion perfectly.

“If this exhibition had a scent, a sound, or a season—what would it be?”

It would definitely be winter. That moment when the light begins to fade after summer and you step outside into that first freeze—the grass is crisp, the air still, and everything feels like it’s holding its breath. That frozen quiet has always stayed with me since I was a kid.

As for the soundtrack, it would be Mount Wittenberg Orca (by Dirty Projectors and Björk) the extended edition. That album captures exactly what I try to express in my work—something raw, emotional, spacious, and deeply connected to nature. It feels like the sonic version of that frozen, magical moment. Nature speaking in its own language.

“What are you currently curious about in your practice? Are there materials or ideas calling to you next?”

Right now, I’m really excited about a new series I’m calling Mon Jardin—it had to be French for some reason; saying “my garden” in English or Icelandic just didn’t feel romantic enough. It’s a collection of smaller textile pieces that come together to form one larger work, almost like a garden of stitched experiments.

These pieces blend traditional techniques with new explorations—some are quite simple, others more intricate—and I’m using them as a space to test textures and forms. I’m also experimenting with salt solutions to help stiffen and shape the textiles. In a way, Mon Jardin is like a mood board of stitches, a growing library of techniques that all sing together in quiet harmony.

“How do you imagine your work evolving in the next few years?”

It’s always growing—I don’t see myself settling into one fixed thing. I think the evolution lies in scale and space. My pieces are getting bigger, and I’m really interested in how far I can push that—how large can something become before it collapses under its own weight? I’d love to create something that fully inhabits a room, something immersive that transforms a space completely. I don’t know exactly where it’s heading, but that’s part of the excitement. It’s changing all the time, and I want to keep following where it leads.

Scent: Lavender/basilica

Song: Mount Wittenberg Orca (Expanded Edition) —Björk and Dirty Projectors

Book: I who have never known men —Jacqueline Harpman.

Item of clothing: Grandmothers leather Jacket.

The exhibition opened on June 7th at the Heimilisiðnaðarsafnið—the Icelandic Textile Museum and will be open until April 2026.

Corran Green— art editor